On Coliving and Tiny Apartments

Wading into the debate between new housing typologies

It’s no longer controversial to believe we need more housing, including more diverse types of housing. This is particularly true for “naturally affordable” units that lower the barrier of entry to the most expensive cities and give young professionals a decent place to live without pairing up with roommates and outcompeting a family for a multi-bedroom unit.

But there’s less clarity on what, exactly, needs to be built.

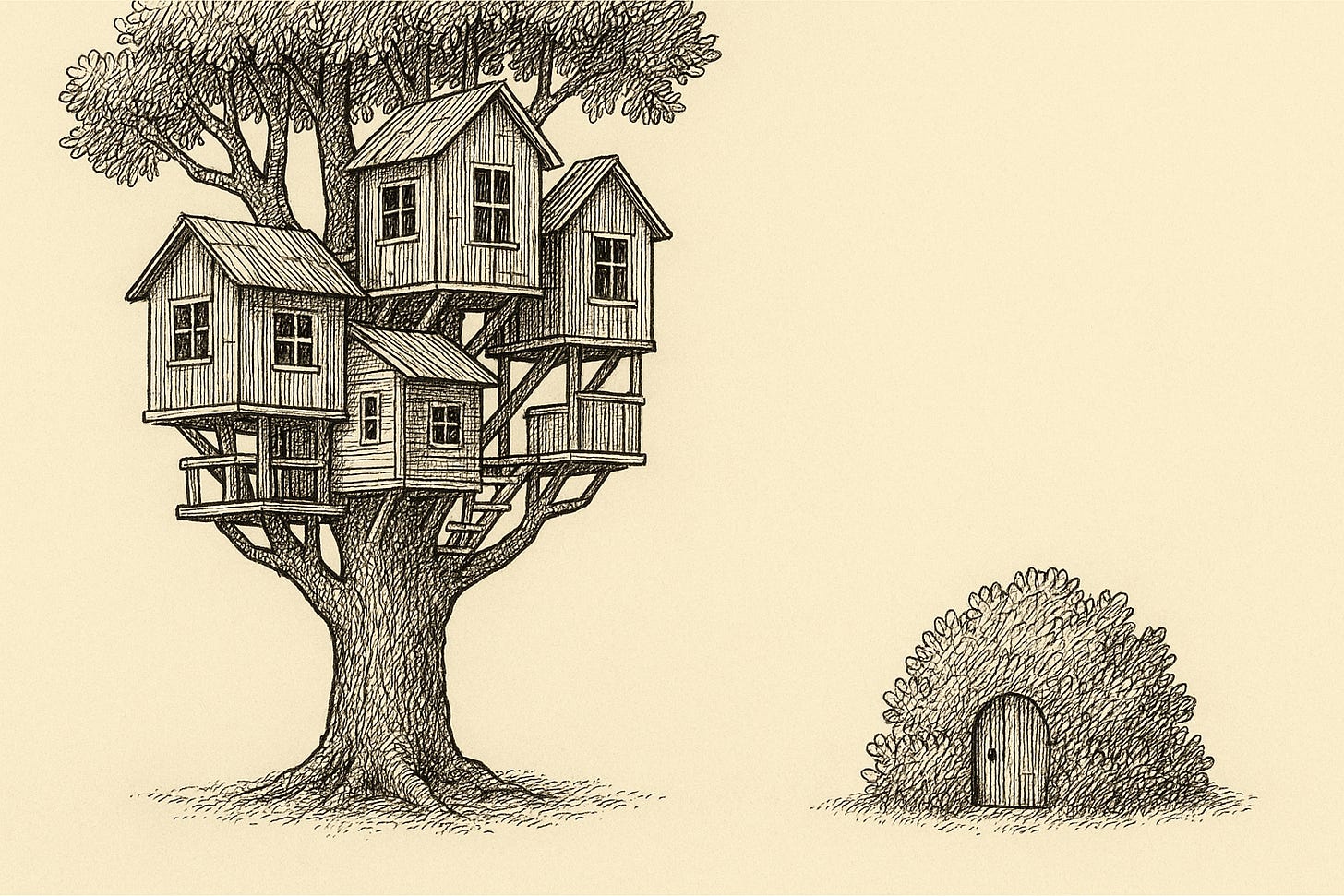

The debate largely breaks between “coliving” versus “micro-apartments”—that is, people who believe we’re better off building big, shared units with each tenant in a private bedroom versus those who believe we should build lots of tiny apartments each with its own little kitchen and bathroom. While each serves a similar need, they differ in some pretty important ways.

I get asked about this a lot because over the past decade I’ve had a hand in the development and management of thousands of units of each, so I’ve seen the upsides and warts of each model. Coliving has ardent supporters and arguments in its favor, but most real estate developers tend to gravitate to the more familiar micro-apartment typology.

In today’s letter I’ll share my observations and take—the good, bad, and ugly of each model, including some stories from the trenches.

What’s a unit, anyway?

Before we dive into the pros and cons, it’s worth spending a bit of time aligning on what, exactly, we’re talking about. To this point, this conversation has probably been confusing to people in the UK who call micro-apartments “coliving” and coliving “shared houses” or “HMOs”. Alas.

Fundamentally, the difference between micro-apartments (small private units) and co-living (private bedrooms in shared units) comes down to how, legally, a “unit” is defined. I know far more about this than I’d like, as coliving operators like Common had to carefully avoid creating an “SRO” (single-room occupancy), which are illegal to build in most American cities. Effectively, this meant ensuring that tenants were “living together” in a unit rather than separately in individual bedrooms. While the law doesn’t define what that means, most inspectors consider either exterior bedroom door locks or kitchen appliances in bedrooms as sufficient evidence that a developer is running an illegal SRO.

In many cases, coliving bedrooms have private bathrooms but rarely, if ever, private kitchens as this would make them legally separate units.

Micro-apartments avoid this dance by simply entitling each room as its own unit. Layout-wise, many micro-apartment developments look similar to hotels: small units in rows along a double-loaded corridor.

While each jurisdiction has its own rules, cities generally enforce a number of minimum standards to qualify a micro-apartment as a legal unit. Each micro-apartment almost always needs its own bathroom and kitchenette, and cities set varying minimum unit sizes—usually ranging from 250 to 400 square feet—as well as minimum dimensions.

Both co-living and micro-apartments can range in terms of quality, access to amenities, and level of programming / “intentionality” in their management. Intentional coliving communities like Radish are a different thing entirely and can be done with either wholly private units (as in many cohousing communities) or shared accommodations (as in Radish).

I. Hot Dogs and Hamburgers

To begin, I’d like to dispense with the myth that one format is objectively better than another from a user experience standpoint. People have different preferences and desires. For some reason, many in the real estate industry tend to forget that fact when it comes to housing. Few things spark more outrage than someone else’s housing preferences being different than one’s own, and many are quick to argue that those preferences should, in fact, be illegal.